As the Lowell Historical Society’s Curator – Ryan Owen – continues his work with the Collection, he will report on the oddities and curiosities that one finds in a collection as old and diverse as this Lowell collection. He’d welcome your comments! Here’s his latest find… (originally posted on his own blog “Forgotten New England)

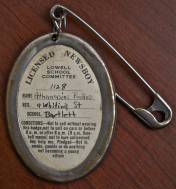

My fingers first brushed across the small metallic oval a few weeks ago. It was right next to Officer Lee’s Lowell PD badge. This very different badge was light, too old to be plastic. I figured it was probably aluminum. As I slid out the drawer at the Lowell Historical Society’s archive, the flourescent overhead lights flashed across its shiny surface, and caught the lettering of the circle of text within. It was a licensed newsboy badge. The diaper pin clip on its reverse looked old, ancient, but it was in remarkable shape. And it carried a name that looked quite familiar to the Lowell political scene – Poulios.

Having delivered newspapers myself in the eighties and into the nineties, something called a newsboy license and issued by the Lowell School Committee seemed really interesting. By the time the 1980s rolled around, we didn’t need newsboy licenses. But, this badge looked more like something a kid hawking papers on a street corner might have had, as in the “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” variety of newsboy. Not the type who slipped the paper under your door on some Thursday evening before dinner and the Cosby Show.

This badge, according to the rules published by the Lowell School Committee, was required to be worn by any minors under the age of 14 before they could sell newspapers on any street or public place within the city of Lowell. And it came with conditions. Newsboys, for as long as they continued to be licensed, were required to attend ‘every session’ of classes at one of Lowell’s schools, unless properly excused from such attendance. Newsboys were not allowed to sell, lend, or give the badge to anyone, or to give any of their newspapers to unlicensed minors to sell for them. The newsboy himself was not allowed to sell newspapers in or near street cars, before six o’clock in the morning or after nine o’clock at night. Lastly, and clearly visible on the badge, newsboys pledged to exemplify behavior becoming of a young citizen, and were not to smoke, gamble, or do anything to jeopardize their image of good behavior.

This newsboy license looked to be early 20th century to me, and had a name attached to it – Athanasios Poulios. These things usually make our artifacts easier to research. And it listed the school that young Poulios attended – the Bartlett. That was slightly less helpful, since the Bartlett school, named for Lowell’s first mayor, traces its roots in the city to 1856 right up to today. Athanasios Poulios’ address, at 9 Whiting Street in Lowell, proved valuable too.

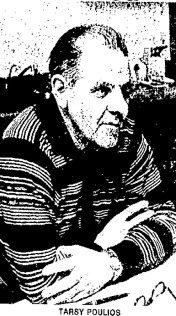

One good rule of thumb when researching the arts and artifacts of the Lowell Historical Society is ‘never assume anything’. During 1992 and 1993 – about the time I was delivering the Lowell Sun to homes in the city’s South Lowell district, Tarsy Poulios was mayor. But, did the badge belong to him? Without a specific year on the badge, I couldn’t be sure.

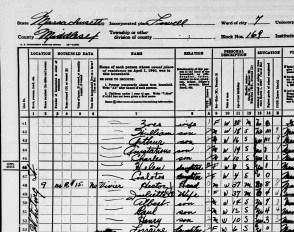

Using the address on the badge, 9 Whiting Street, I found the Poulios family living there during the enumeration of the 1940 US census. With a quick process of elimination across his four brothers, I was able to confirm that Tarsy was a nickname for the ‘Athanasios’ whose name was printed on the front of the badge, and in the census. I already knew that the badge couldn’t have belonged to one of his sisters since, among the many rules attached to these newsboy licenses by the Lowell School Committee, one specifically stated that ‘licenses shall not be issued to girls, nor to boys under the age of ten years.’

All of that dated this newsboy license to the late 1930s or early 1940s, meaning that the badge represents one of Tarsy’s first jobs. It dated to a time long before his two-year run as Lowell’s mayor in the early 1990s, and before he joined Lowell’s City Council in 1987. Tarsy wore the badge decades before he even began his political career as a neighborhood activist with the Acre Model Neighborhood Organization, and the Community Development Block Grant Organization before that.

When he died in 2010, Tarsy was recalled as gruff, adept at defending his arguments, and very proud of his roots in the Acre neighborhood (he called it ‘God’s Acre’) and in Lowell’s Greek-American community. He was elected to City Council on his platform of improving Lowell’s neighborhoods, and had a specific focus on removing abandoned cars from city street, something that Lowell struggled with during the 1970s and 1980s.

A few years after Tarsy was selling newspapers, he graduated with Lowell High School’s class of 1943, and went on to serve his country during World War II when he entered the US Army and saw combat action in Japan, the Philippines and Korea. He was honorably discharged as a Sergeant in 1946. When he first came home from the war, he attended an electrical school in Boston, but left when his father died and returned home to Lowell to work in the Merrimack Mills to support his family. By the time the Merrimack Mills closed in the 1950s, Tarsy had moved on to become a letter carrier, a job he held until he retired in 1984.

As Lowell’s mayor in the early 1990s and throughout his career as a public servant before that, Tarsy most enjoyed helping his constituents who he fondly called Joe and Joan Sixpack, whose parents he delivered mail to for over thirty years, and whose grandparents he sold newspapers to, way back in the 1930s, at the very start of his storied career. His newsboy badge has held up well, in the 85 years or so since he wore it, selling newspapers in the city he would one day lead. Its vintage-looking clip looks as if it could still hold the badge to someone’s coat. And its shiny metallic holder looks much more valuable than the 25-cent replacement fee that Tarsy would have had to pay in order to get a duplicate badge, had he lost it all those years ago.