As Lowell Historical Society curator Ryan Owen continues to guide us through the Society’s collection, making things orderly, noting his finds and preparing for new donations, he offers this treasure from the archive – the wooden stake. Of course there’s a story!

From the Curator’s Desk: The Wooden Stake in our Collection

During these last few weeks, we’ve been busy at the Lowell Historical Society. As we near the end of our 2013-2014 year, we had our annual meeting last weekend at Lowell’s Pollard Memorial Library where our society’s Vice President Kim Zunino spoke about some of the fascinating finds she’s encountered in the attic of Lowell’s City Hall. With our new year, we are also welcoming a new member, Kathleen Ralls, to our board. And, last, but never least, we continue to work feverishly on integrating new collections and artifacts into our archive. Look for more on that soon!

Naturally, as we move into the future, we continue to study the past. And in processing, organizing, and better cataloging our collection, we find some pretty intriguing items. Take this one, for instance:

At first glance, it looks like an old wooden stake, rounded, with some fire damage evident at its edges. The stake looks old, feels old, but still retains just a hint of a smoky, burnt wood sort of odor.

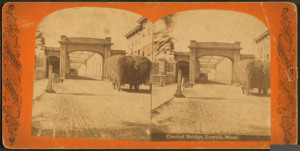

But, before you ask. . . No, it’s not one of the last surviving wooden stakes left over from the Victorian vampire epidemic rumored to have hit Lowell in the 1890s. It’s actually a wooden pin retrieved from the ruins of a fire that ravaged Lowell’s Central Bridge on August 5, 1882. Although largely forgotten today, the fire caused quite a stir in Lowell back in those days.

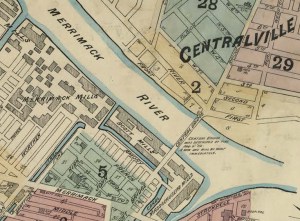

Much better known today as the Bridge Street Bridge, the span connecting Lowell’s Centralville section with its downtown mainly goes unnoticed these days, except for the occasional traffic jam which gets it into the news. These days, when the cars begin to back up, you can drive your car along the river for a couple of extra minutes, and cross the Merrimack River at the Aiken Street Bridge, or at the Hunts Falls Bridge.

But, when the Central Bridge burnt down on that August night 130 years ago, folks who found themselves on its Dracut side had a real worry. How were they going to get to work?

In a time before vacation days, workers who walked the Central Bridge to earn their bread in Lowell’s mills watched in disbelief as flame consumed the bridge in 1882. The first of them noticed the fire in the quiet of a summer night, just a few hours before sunrise when the first flames were seen at the south end of the Central bridge, the section closest to downtown.

When he saw the flames, he ran and told the nearest policeman, who ran to the nearest fire alarm. The fire brigade came soon after, but their progress wasn’t fast enough to prevent the spread of the fire beneath the bridge. As they made their valiant efforts to put down the fire on top of the bridge, the flames spread nearly half its length underneath.

The men slung the fire hoses across the bridge, and also battled the flames from the nearby Boott mill. Another hose carriage fought the flames from the Centralville side. The fire kept advancing, though, and just an hour later, flames were engulfing the entire span of the bridge, and lighting up the night sky.

From the downtown end of the bridge, the firemen made one last push to save the structure, climbing into the burning bridge, and trying to put down the fire. They fought until the end, until the bridge itself failed and fell into the river below, throwing five firemen into the dark waters with it.

– James Halstead, foreman, Hose 4

– Edward Meloy and William Meredith

– William Dana, Steamer 3

– James McCormack, Hose 6

A sixth man, Capt. Cunningham, who had been fighting the flames from the roof of the bridge, caught onto the cross bar of a telephone pole as he fell and clung to it until he was rescued. All of the men survived, but several sustained injuries.

As the bridge failed, spectators on both sides of the bridge watched a gas pipe explode in a blinding flash as firemen called out to their brethren in the dark waters below. They feared for the men flailing about in the water. They also feared that the Boott or the Massachusetts mills would be next. They shuddered as their watched the windows of the Boott mills smolder, and then ignite.

During the fire, and the days and weeks following, all speculated on what might have caused it. The going theory was that it had been caused by the sparks thrown off by some machinery used by the Boott mills. Some even came forward to say that they had seen the bridge catch fire a few days before, and that workmen from the mill had put it out.

In the end, though, it didn’t matter. The bridge was a total loss, leaving more than 8,000 Centralville residents cut off from Downtown Lowell and their livelihood. Those with horses, the wealthier in Centralville, were able to go a few minutes out of their way and enter the city by the Pawtucket bridge, but most of the people who depended on the bridge walked to work. And they were out of luck.

The only way left across the river appeared to be by boat, which harkened back to the days of Bradley’s Ferry, before the bridge was built. In the days following the fire, the City Council discussed and approved plans to lay a footbridge across the ruined bridge’s span. It was quickly put into place, and Centralville residents were thankful – even if it didn’t have a cover, which drew a little bit of ire among Centralville residents. By March of the following year, townspeople were known to remark that the builders of the old bridge knew what they were doing when they made it a covered bridge.

The relics of the old bridge quickly became popular. A January 1883 Lowell Sun article recounted how City Marshal McDonald was presented a ‘finely finished white oak club’ made from the timbers of the old bridge, which had been under water for 54 years. The novelty of the ruined bridge wore off quickly, though. Lowellians grew impatient with the builders as the months following the fire wore on. By September 1883 a Lowell Sun writer stated that ‘whoever drew up the contract between the bridge company and the city of Lowell for the bridge’s iron work ought to create a new one, and then tie a handkerchief around his eyes and jump into the river.” The writer went on to say that the delays had hurt Centralville residents and city traders, and that the contract offered the city no recourse in addressing the delays in the construction of the bridge with the builders of the bridge.

In the end, though, the bridge reopened. It took almost a year, but a new iron bridge reopened in the old wooden bridge’s place. That bridge stood for over half a century, before being washed away in the Flood of 1936, and replaced by the bridge that still stands today.

And that’s the story of the wooden pin in our collection, contributed and tagged so long ago. (The tag itself is almost as interesting as the pin itself.) The pin is just one of the items in the collection that we’re currently researching.

Watch here for future updates on other items we find in the collection.